(Editor’s note: Richard Perske is the author of “Boom Town to Ghost Town: The Story of Fulford.” Since the book was published in 2015, Perske continues to dig deeper into the history of this Eagle County mining camp at the base of New York Mountain.)

Prospecting at the End of a Rope

By Richard Perske

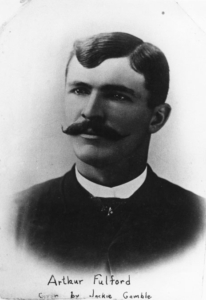

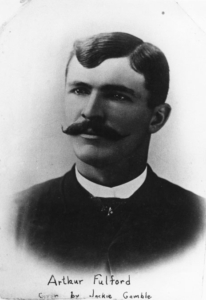

Arthur Fulford, the daredevil prospector. (Courtesy ECHS and EVLD)

Art Fulford read the Leadville Herald Democrat of January 1, 1886 with a great deal of pride and personal satisfaction. The article titled “EAGLE’S CAPITAL” and described in great detail the town of Red Cliff, the county seat of Eagle County. The article cited several of Fulford’s recent achievements and gold mining successes. Nearby Battle Mountain was finally booming again and largely because of him. Art could well remember his earlier and less prosperous times in Colorado. Red Cliff had a pretty humble beginning as well.

Red Cliff had been established in 1879 and at that time was a remote silver mining camp in Summit County, accessed by trails and a very bad wagon road to Leadville. Red Cliff had its ups and downs as the silver mines on Battle Mountain were first discovered and the area boomed, then slumped. Early on, mine speculators and bad luck damaged the reputation of the town. However, everyone had faith in the mineral treasure in the Battle Mountain mines. Even that faith would soon be sorely tested.

The nearby Holy Cross Mining District had initially showed great promise as a gold producer. Numerous veins showing free gold had very good initial assay results. Speculators quickly sold their claims to large companies who made major mine investments, only to discover that the gold content diminished significantly a few feet below the surface. Eons of natural weathering and erosion had concentrated the gold mainly near the surface. The mining companies soon went bankrupt and pulled out, contributing to a general slump in Red Cliff mining investments.

Red Cliff had become noticeably cash-poor by late 1881 and the merchants were forced to extend credit to many customers. Mining was very risky business and the local smelter operation was a large part of the problem. The Battle Mountain Smelter Company in Red Cliff refined the silver ore output from the mines and was in dire financial difficulty. The smelter closed in March 1882, owing its workers four months unpaid back wages. The workers, merchants, and suppliers were owed nearly $40,000 and were very angry. The smelter’s financial manager F.C. Garbutt, unable to satisfy their demands for payment, wisely secured a horse and left town just ahead of a growing mob. That night the mob paraded on Eagle Street and lit a large bonfire to burn Mr. Garbutt in effigy. This was only the first blow to the town’s economy. The Belden mine, the area’s best producer, was also forced to close and a dispute among the Denver owners put the mine in an extended period of receivership. Many Red Cliff men were idled and out of work in 1882. The economic slump would last at least 12 months.

On the night of September 22, 1882 nearly half of Red Cliff burned to the ground as the result of a disastrous fire that started at the Southern hotel, saloon, and dance hall located in the Strand building on Water Street.

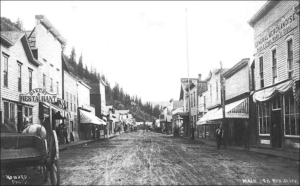

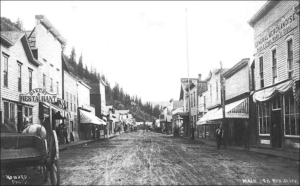

This turn-of-the century photo shows a bustling Red Cliff business district. The Quartzite Hotel is on the right side, middle of the photo. (Courtesy ECHS and EVLD)

Red Cliff managed to slowly rebound from these early misfortunes. The State Legislature established Eagle County in late 1883 and Red Cliff, the only town, became the county seat. By then the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad had finally reached Red Cliff providing essential ore freight, scheduled passenger coaches, and telegraph service to Leadville and the world beyond. The Battle Mountain lead and silver ore was now being shipped by rail to Leadville smelters. However, it was the efforts of a “daredevil prospector” named A.H. Fulford who found gold in the quartzite cliffs of Battle Mountain in 1884 that finally put the town back on its feet.

On October 12, 1884 Art and two partners discovered and located the Ben Butler mine high on a remote unclaimed cliff section of Battle Mountain. Bob Haney and Will Travers lowered Art on a rope to investigate the high cliff crevices and openings in the quartzite formation. He found a fissure vein that yielded high grade free-milling gold ore. Art sacked the ore and they hauled it up the cliff by rope. Art soon became known as “the daredevil prospector”. By December they were shipping the first gold ore produced from the Battle Mountain quartzite contact and a new gold rush was on. The Ben Butler quickly developed into a big gold producer and the partners were getting rich. In 1885 Art used some of his proceeds to buy interests in other nearby quartzite mines including the Gold Wedge, Golden Wonder, and Percy Chester. He also took on several local partners to help finance the costs of mine development. All of these mines became very good gold producers and Art was soon supervising 45 men developing the remarkable Percy Chester mine.

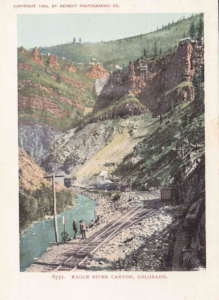

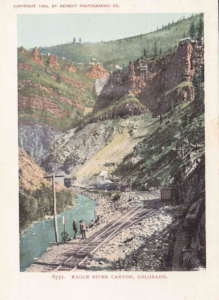

This 1898 postcard shows the D&RG Railroad narrow gauge track in Eagle River canyon. The Ben Butler mine is visible among the sharp-pointed rocks in the upper right corner. (Courtesy ECHS and EVLD)

In the two years prior to Art’s discovery the annual production of the Battle Mountain mines in both silver and gold was about $500,000. In 1885 gold production had doubled and in 1886 gold production alone would reach $420,000. Total ore production for 1886 would exceed $1,000,000. The economic impact of Art’s Ben Butler gold discovery on the town of Red Cliff and Battle Mountain mine production was huge. The cliffside quartzite gold formation was no longer being ignored. Red Cliff even had a new hotel named “The Quartzite.”

The discovery of rich gold ore in the Ben Butler quartzite spurred the development of other nearby claims that had not previously been worked. Renewed exploration of the quartzite fissure veins had quickly doubled the value of gold output on Battle Mountain, entirely due to Art’s amazing discovery. The nearly inaccessible claims in the quartzite cliffs formed a narrow band just below several well-established silver mines, the Eagle Bird, the R.L.R., and the Belden. Art and his brother Mont took a lease on the nearby Ground Hog mine and made a considerable gold strike there as well.

Art supervised the construction and development of the Percy Chester mine and employed 45 miners. They constructed a 750 cable tram to deliver ore to the D&RG tracks below. When the miners encountered a large, flooded cave with promising ore, it was pumped and drained and the valuable heavy, wet ore delivered to a trackside building and dryer that Art devised. The mine machinery, ore trams, and pumps were run by steam engines.

In the spring of 1886, the camp was finally prosperous and booming again largely due to Art Fulford’s gold discovery in the quartzite. People were optimistic and many were sharing in the riches of Battle Mountain.

This drawing of Battle Mountain mining claims appeared in the Leadville Herald Democrat newspaper on June 1, 1890. The Ben Butler claim is on the right. (From the Colorado Historic Newspapers website)

(Want to learn more about Eagle County’s early mining days? Rich Perske’s “Boom Town to Ghost Town: The Story of Fulford” book may be purchased from the Eagle County Historical website, or at several retail outlets in the Eagle Valley.)