Valentines Day 1886 : A Lynching at Red Cliff

Researched and written by Rich Perske

In 1879 Red Cliff was a rough mining camp consisting mostly of tents and a few crude cabins. It quickly grew to be a respectable little town with a busy commercial center and in 1883 became the Eagle county seat. Red Cliff was becoming a prosperous town that dealt firmly with the “criminal element” to maintain law and order. On Saint Valentines Day 1886 a lynch mob descended upon the town, broke into the jail and hanged a man accused of murder. This lawless act immediately brought statewide scorn to Red Cliff. However, many thought it was swift justice for the senseless murder of a Battle Mountain miner by a drunken bully. The lynching of “Missouri Jack” caused quite a stir and a defiant Jack Perry found fame at the end of a rope.

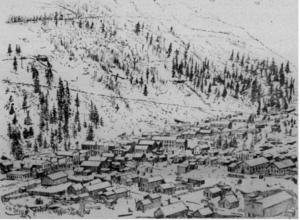

Red Cliff and Horn Silver Mountain:

This sketch of the bustling Red Cliff mining camp appeared in the Leadville Democrat Herald newspaper on June 1, 1890.

January of 1886 began with a very optimistic outlook for the Battle Mountain miners and Red Cliff. Recent gold strikes were producing significant wealth and steady employment. The “good times” had finally arrived, but so had winter. The winter of 1885-86 brought unusually heavy snow and bitter cold throughout Colorado. Avalanches ran in the Eagle River Canyon and Ten Mile Canyon in January and February, disrupting train service to Leadville and Denver. Between work shifts the miners crowded around stoves in cabins and saloons to keep warm while playing cards, drinking, and gambling to pass the time. Living and working in these winter conditions was difficult and some of the miners were getting quarrelsome.

The thriving town of Robinson was just east of the Eagle River headwaters on Ten Mile Creek and about twice the size of Red Cliff. (The ghost town of Robinson is now under a lake formed when the Climax mine tailings piles were reclaimed.) Several very successful silver mines were in operation there including the Wheel of Fortune mine. Robinson was located 20 miles from Red Cliff by way of a narrow mountain trail along the upper Eagle River drainage. Riding the Denver &Rio Grande railroad over Fremont Pass to Leadville and then over Tennessee Pass to the end of the line at Red Cliff was a longer, but much safer trip in winter.

Jack Perry

In January a young and inexperienced miner named Jack Perry began working in Robinson’s Wheel of Fortune mine as a “mucker,” filling ore carts at the bottom of the mine incline. The loaded ore carts were pulled to the surface, dumped and returned for another load. Twenty-one year old Jack Perry was from a well-to-do family in Independence, Missouri and had a bit of an attitude problem. He also owned a .44 caliber nickel-plated Hopkins and Allen six-shot revolver. His 27-year-old brother, Willard, had arrived in Colorado several years earlier and was employed by the D&RG at Salida as a telegraph operator. Willard C. Perry was well thought of in Salida and liked by all his coworkers. However, his younger brother Jack was considered the black sheep of the family. Jack was described as a “hot-blooded” fellow who became belligerent and violent when angry or drinking. He could be a real hellion and bully. Young Jack admired Missouri’s famous rebel outlaw Jesse James and carried a gun that was one of Jesse’s favorites. He also developed a taste for saloon whisky and western dime novels, a very dangerous combination.

On Monday, Jan. 25th, Perry was carelessly loading the ore carts and the hoist operator was having trouble dumping some of his loads. The overloaded carts would hang up, requiring extra time and effort to dump them. At mealtime the operator asked Perry to pay attention to loading and not overload the cart. They exchanged some angry words. Later when the problem was not corrected, the ore cart suddenly returned down the incline and Perry had to jump back to avoid being hit. Furious, Perry raced to his cabin for his gun. When he returned, Perry found the operator at another task. Perry brandished his gun, cursed, and threatened to kill him, then pistol whipped the man severely, leaving him semi-conscious on the ground and bleeding profusely from three deep gashes in the top of his head.

Believing that the man’s head injuries could be fatal, Perry hastily grabbed a few belongings and fled Robinson. The hoist operator was taken to Leadville for medical treatment and was unable to work for well over a month. He claimed he had been called away to another job and that a less experienced man had lowered the cart that nearly hit Perry. Perry committed this armed assault in Summit County and jumped a train to hide out in Leadville (Lake County). He later slipped into Eagle County and eventually reached the end of the Rio Grande line at Battle Mountain. Perry was on the run from the law and laying low. On February 11th he was drinking heavily at Lou Deering’s saloon at Belden’s camp on Battle Mountain. The next morning a strong winter storm moved in, for the next two days, halting train traffic from Leadville. The blizzard lifted late on Saturday, followed by bitter cold.

Winters were fierce in Red Cliff, as indicated in this undated photo of Eagle Street.

The murder

Perry later testified that he coincidently met Lou Deering, age 27, at Battle Mountain and that they were old school friends from Missouri. Deering and Perry drank at the saloon on Thursday night and Perry slept that night in the saloon. On Friday morning he and Deering resumed drinking and he remained in the saloon all day. He was down to his last 20 dollars. The saloon, a small wood frame building, and known locally as “the Little Church,” was situated on the road between Gilman and Bell’s camp. The story unfolded with the sworn statements from five witnesses presented to Justice of the Peace Arthur Helm. The witnesses all testified to essentially the same facts :

On Friday evening , February 12, between 3 and 4 o’clock in the afternoon, Lou Deering, Fred Bayha, J. L. Caruthers, and J.M. Goolsby, were in Deering’s saloon, and they noticed that Mike Gleason and Jack Perry were talking in a friendly way together. They had been drinking considerable whiskey, and both Perry and Gleason were under the influence of liquor. Perry would pull out his revolver occasionally, saying what a good shot he was and by way of proving it, would fire a ball through the roof and the side of the wall. All of the witnesses say he shot through the side of the building at least twice. About three o’clock Gleason asked Perry to loan him five dollars. Perry immediately took a twenty dollar greenback and handed it to Gleason. A short time elapsed when he asked Gleason to give him his change. Gleason said, “You are too drunk now, Jack. I will give it to you tomorrow.” “Give it to me now, I want it.” roared Perry

“You shut up or I’ll whack you in the jaw” was the reply.

“No I won’t shut up. I want my money” said Perry brandishing his revolver by his side.

“Let me have my money now, I want it.

“No I won’t ” said Gleason. I’ll give it to you to-morrow, when you are sober”

Those were the last words Gleason ever said, for Perry struck him on the side of the head with the revolver. Gleason walked toward the door, with Perry following. Gleason turned to open the door and Perry shot him in the breast. Gleason had opened the door by this time and fell out of it down to the ground. Perry stood over him and fired at him again, but must have missed him as the only shot that entered his body was the first one fired, and this one entered his breast. He then put his hand in the hip pocket and fumbled around for something. When he drew his hand out a $20 bill, three dollars and fifty cents in silver and a pocketknife fell to the ground.

Judge Helm’s recorded witness testimony

Perry had been drinking for two days and apparently not eating much. Gleason had just come in that afternoon for a few drinks and a card game. Perry’s drunken pistol shooting must have annoyed and disturbed the men enjoying their Friday afternoon of relaxation and drinks. As he reloaded his gun, Perry reportedly said “these two are for the old marshal at the Cliff, ” referring to Marshal Tom Evans. One man had just left the saloon to begin his work shift at a nearby mine. It appears that Mike Gleason had used the excuse of a $5 loan in an attempt to get Perry to stop drinking. When they later searched Gleason’s body he was found to have $78. Gleason had no need to borrow $5 except to try to quiet the very drunken Mr. Perry. It was a fatal miscalculation.

That Sunday (Valentine’s Day) the following column was published in Leadville:

Mike Gleason’s Character

Mike Gleason, the man who was killed in Red Cliff by Perry, was well and favorably known in both Leadville and Aspen. He has been what is known as a lucky miner, and sold an interest he had in a mine in Aspen a few months ago for several thousand dollars. After this he came to Leadville and sojourned here sometime. Judge Rose met him in this city, and gave him a tenth interest in the Printer Boy mine at Red Cliff. About the first of January the men working in the mine struck a nice body of ore that has been assaying fifteen ounces silver and one ounce gold, and Gleason it is said, was offered $1,000 for his tenth interest in the mine shortly before he died, and refused it. Although Gleason went on incipient sprees occasionally, his reputation for peace and quietude seems to have been the very best. He has been known for many years to Alderman C.C. Joy and others in this city, and this is the character that they give him.

A resident of Red Cliff, in a chat with a reporter of this paper, says that Perry was crazy with drink when he shot Gleason through the brain. Of course this is not mentioned by way of excuse for the terrible crime for which no palliation has so far been offered.

Leadville Herald Democrat February 14, 1886

The unarmed Mike Gleason had been senselessly murdered by an arrogant young drunk. Gleason,40, may have had his faults, but he was a family man. He and his wife, Barbara Quirk Gleason, had been married 16 years and had three children. Their oldest son Tom was 10, daughter Kate was 7 and youngest son Frank was 4. Their home was in Leadville, but Mike had interests in a mine on Battle Mountain, as did his relatives. His father-in-law, Dennis Quirk, owned a Battle Mountain mine nearby at Rock Creek. Molly Quirk Fulford was his sister-in-law and Art Fulford was his brother-in-law. Art Fulford operated three mines employing almost 100 miners within a half mile of Belden’s camp and was one of the area’s leading citizens. It is little wonder that the Battle Mountain miners were extremely angry and soon began talking about lynching Jack Perry for murdering Mike Gleason.

Running from the law

Immediately after the shooting, Perry grabbed his money from Gleason’s pocket, took another $20 from Deering and fled towards Red Cliff. He intended to skirt Red Cliff and get back to Leadville, but was hampered by drunkenness and snow. Goolsby and Bayha had quickly left the saloon and headed towards Red Cliff to report the murder. Perry caught up with Goolsby and forced him at gunpoint to lead the way and break trail through the snow as they descended into the canon in order to follow the railroad tracks. Perry hoped to take the road up Homestake Creek to Leadville. Bayha had ducked into a tunnel, taken a different route, and reached Red Cliff first, alerting Marshal Tom Evans. Evans was waiting with a drawn gun when Perry and Goolsby arrived at the railroad bridge below Red Cliff. He arrested Perry without further incident. Perry was in custody for nearly two hours and “was most nonchalant and asked at once for a dime novel and a pint of whisky, and declared that his neck was not made for a rope, and that his father had too much money to let any harm overtake him. He also boasted that he “did” three men at Cheyenne and one in Denver.” Perry’s lack of remorse and arrogant statements were soon public knowledge, interpreted as a clear admission of guilt and an expectation that his family’s wealth would free him. News of his arrest for murder was telegraphed to Perry’s brother in Salida who acted immediately and soon had legal assistance on the way.

Willard Perry and his friend Jake Bergeman traveled from Salida to Leadville on the Saturday morning train where he hired a well-known defense attorney and judge. Judge Rice was a tall man with a commanding courtroom presence and extensive experience in defending criminal cases. They knew that Perry’s murder case would be difficult to win if tried in Red Cliff. they would need a change of venue. The wheels of Perry’s defense were already in motion but the Saturday Rio Grande train to Red Cliff had been canceled because the blizzard had blocked the tracks. The three men had to wait out the storm.

Men watch a rotary snowplow clear the railroad tracks in order to open up the line for rail traffic.

Back in Red Cliff, sworn statements and evidence were gathered. As facts became more widely known, the talk of lynching Perry grew stronger. Angry Battle Mountain miners huddled in groups around saloon stoves. Justice Solon N. Ackley collected testimony and evidence. The 20 dollar greenback at the root of the dispute had been issued by the Bank of Boston. Judge Ackley took the notorious bank note as a souvenir and substituted one of his own.

By Saturday afternoon the storm was slackening, the sky was clearing, and the temperature was dropping towards zero.

William Greiner, Eagle County Sheriff from 1887 – 1891.

Sheriff William Greiner was now in charge of the prisoner and he sensed danger in the gathering crowds. Anticipating a possible Saturday night lynching party, he secretly moved Perry out of the jail to a private residence. The night passed without incident and the Sunday morning Leadville train managed to arrive in early afternoon, bringing W.C. Perry, J. Bergeman, and Judge Rice. Judge Rice interviewed and counseled Jack Perry and then took his sworn statement for the record. Rice also requested a change of venue and permission to take Perry to Leadville for trial. At that time Judge Ackley saw no reason to grant his request.

Jack Perry’s carefully prepared statement contradicted the eyewitnesses’ testimony. He said Gleason had aggressively advanced on him and cornered him, forcing him to shoot. He described Gleason as a known fighter. Perry claimed that he had recently been beaten by three men in Cheyenne and had vowed to never to let it happen again. Perry also denied forcing Goolsby to break trail, claiming that he was headed to Leadville to turn himself in to the authorities there. Perry’s brother offered well-rehearsed excuses to anyone who would listen to him: Jack had had a severe ear infection as a child that caused him to act crazy when sick or drinking alcohol. Jack was a tee-totaler prior to coming to Colorado and drinking at high elevations badly affected him. Jack was not in his right mind now or when he shot Gleason. Jack Perry was insane.

The Battle Mountain miners knew that Jack Perry was a dangerous, gun-crazed bully when he was drinking. It was clear to them that the Perry family had plenty of money and intended to free Jack using the old insanity dodge. The miners were now determined to present their case to Judge Lynch and to do it quickly. By late afternoon even Judge Ackley sensed their growing anger and smelled danger. Ackley agreed to the change of venue and prepared the witness statements for a transfer of jurisdiction. Sheriff Greiner agreed to immediately release Jack Perry if a special train could be summoned from Leadville. W.C. Perry agreed to pay the $100 fee for a special Rio Grande train to be dispatched from Leadville that day. Greiner also deputized as many of the town’s responsible men as he could find who were willing to assist him. Things were getting hot in town as the sun set, but the thermometer was headed to zero and would soon go well below. Judge Lynch began hearing the miner’s appeals in the saloons and large crowds of miners were gathering for action.

Although the jail referred to in this blog may have been a different building, this is the historic jail that remains in Red Cliff currently.

The plain stone Red Cliff jail was located on a rock bluff across the Eagle River on the south side of town just above the railroad tracks and accessed by a bridge. The Rio Grande train depot and locomotive water tank was a quarter mile further up the river. That night the sky cleared, and a three quarter moon reflected off the snow like daylight. The special train from Leadville arrived at the depot about 10 p.m. enveloped in a cloud of smoke and steam. The temperature was 10 degrees below zero and dropping. The shrill locomotive whistle and a hiss of escaping steam announced the start of the action.

The lynching of Jack Perry

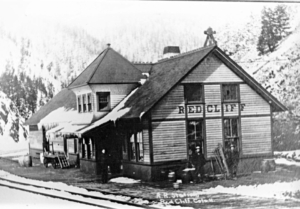

D&RG train Depot at Red Cliff.

At the railroad depot, Deputy Sheriff Fulford and Jake Bergeman boarded the coach car that was to carry Jack Perry to Leadville. W.C. Perry climbed on top of a freight car, directing the engineer to stop at the jail where Sheriff Bill Greiner and Jack Perry would be able to quickly board. The train advanced towards the jail, but some empty freight cars, frozen solid to the tracks, blocked the way. The engineer broke the locomotive pull bar in repeated attempts to bump and dislodge the frozen cars. He started to back to the roundhouse to reverse the engine and try again, but fate intervened. A large mob had already begun attacking the jail and seeing this, W.C. Perry jumped down and ran to his brother’s aid.

At the trackside jail a mob of 200 miners demanded that Perry be given over to them. Sheriff Bill Greiner was inside, well-armed and determined to resist. He said he would sell his own life dearly before giving Perry up and they should damn well keep back. That’s when he heard the mob call for giant powder (dynamite) and noticed the pounding of hand drills attacking the stone jail walls. Not wanting to be blown up, Greiner opened the door and was immediately knocked to the floor. The lynch mob grabbed Jack Perry and began marching him out of town and up the tracks a quarter mile to his fate. His brother reportedly tried to intervene and hand him a gun, but he was disarmed and restrained by the mob. On the long, cold walk Perry was combative and asked if they were trying to freeze him to death.

Railroad water tank at Minturn, similar to the tank in Red Cliff where the mob hanged Jack Perry.

The lynch mob was cold, disorganized, and fueled by alcohol. No one had brought a rope. As they passed the locomotive they cut the bell cord rope off and proceeded to the tall Rio Grande water tank where they hanged Jack Perry from a ladder rung. Perry’s body was left hanging until after midnight when his brother finally cut him down.

Valentine’s Day had passed, and Jack Perry’s life had ended just like the bad men in his dime novels, at the end of a rope. The D&RG railroad had supplied the gallows and his own brother had supplied the rope. On Monday his body was taken to Leadville to be embalmed and his brother accompanied it back to Independence Missouri for burial in the impressive Perry family plot. Perry’s funeral and his family’s grief were later reported in the Leadville papers, noting “the family is quite well off and stands very high in the community.” Mike Gleason’s funeral service was held on Wednesday, February 17 in Red Cliff with a very large number of people in attendance.

Newspapers throughout Colorado quickly reported and denounced Perry’s lynching at Red Cliff and strongly criticized the town. The headlines proclaimed “A LYNCHING BEE AT RED CLIFF ! ” The townspeople correctly pointed out that the lynching was not done by them but by the Battle Mountain miners. In the weeks that followed, the Leadville newspapers carried numerous articles updating the facts and developments concerning Gleason’s murder and the sensational lynching of Jack Perry. A group of Leadville newsboys even penned a popular play titled “The Lynching of Missouri Jack” with a very creative and fictional plot, selling a lot of newspapers.

A Lynching Bee at Red Cliff

Special to the Tribune-Republican

RED CLIFF, Colorado, Feb. 14. —- A mob numbering about two hundred came into town earlier this evening, overpowered the Sheriff, and took Perry, the man who killed Mike Gleason on Battle Mountain day before yesterday, out of jail and hung him from the railroad water-tank at 10:45 p. m.

His only request was to be allowed to climb the ladder and jump off, but this request was denied. He was drawn up a short distance from the ground by the hooting mob and strangled to death. No man ever died more game.

The officials getting word of the coming of the mob late this afternoon, telegraphed to Superintendent Cook for an engine to take the prisoner to Leadville, but it was met at the depot and taken possession of by the mob.

The populace is greatly excited, but the mob has dispersed, and all is quiet now. The body is still hanging at 12 o’clock midnight.

In addition to reporting the details of the Perry lynching, the opinions of several prominent Red Cliff citizens were published :

A.R. Brown, county attorney : “I was retained on the defense, and think that the plea of insanity would have cleared him; but the deed is done, and everybody concurs in the action of the mob, I have no blame to attach.”

Dr. A.G. Mays : ” We all feel that the fate was deserved and that the Battle Mountain miners vengeance was as merited as it was vigorous.”

Robert Haney : “Yes, I know some of the people of Robinson say the bounds of propriety were overstepped, but they should remember that this retributive act was not for deeds done at Robinson, but for the murder in cold blood of an inoffensive Battle Mountain miner.”

Thomas Randall : “I don’t care to say, but in view of the expected influx of people, it would certainly have a deterrent effect upon the bullies and rounders always in the advanced guard.”

- N. Ackley : “It was a perfectly orderly crowd. I looked on from my office door and I can say I did not see a drunken man in the party, and if Judge Lynch ever executed a righteous judgment he did it that day.”

Leadville Herald Democrat

February 20, 1886

On February 19, George S. Irwin, the editor of the White Pine Cone in Gunnison county managed to summarize the entire affaire in just two brief lines:

Mike Gleason, a miner, was shot dead at Red Cliff last week by a man named Perry. Cause, whisky.

The remains of Jack Perry, the man who was lynched at Red Cliff, were taken to Leadville for burial.

(In 1893 George S. Irwin would move his family and printing press to the gold rush town of Fulford and establish its only newspaper, The Fulford Signal.)

A reporter had asked miner Tom Baynard why he referred to Red cliff as “a poor man’s camp” ? Mr. Baynard had some very wise and interesting observations:

“Because a poor man can make good wages working those prospects from the grass roots. Whether you get into the porphyry or quartzite it pays. There is not an idle man in the camp, and there need never be if they want to work. It requires a comparatively small outlay to begin to work a mine in Red Cliff to what it does in other camps. Just compare it for a minute to Aspen. There you have to spend from fifty to one hundred thousand dollars before you can get out any pay ore.

In Red Cliff a couple of Swedes started to dig on Battle mountain about January 1, and they are shipping pay ore already. This is the reason there is going to be a tremendous boom in the camp in the spring. The miners have learned the nature of the displacement there and some of them have got right into the quartzite and struck the main body of the ore, which simply means a fortune for all who have done it. It seems to me, I mean so far as the result is concerned, like placer mining used to be in California. If a man don’t want to work his claim on Battle mountain he can generally sell it for a fair and reasonable price.

Is the town growing ?

Yes, it continues to grow even during the winter. You bet it is quiet over there. Since Missouri Jack was lynched people have left their doors unlocked, and if a sneak thief happened to be in town he wouldn’t dare to open a door or touch even a stick of wood. Lynching may not be what the lawyers would call the correct thing; but it helps the camp wonderfully and makes a jail a useless ornament to the town, and cuts down the sheriff’s and city marshal’s fees to nothing. Yes, sir, Red Cliff is a very orderly place and we propose to keep it so.”

The Leadville Daily/Evening Chronicle

March 1, 1886

This man on the street interview presented a good overview of the situation in Red Cliff in the spring of 1886. The camp was finally prosperous and booming again largely due to Art Fulford’s recent gold discovery in the quartzite. People were optimistic and many were sharing in the riches of Battle Mountain. The lynching of Jack Perry had brought severe criticism to the town, but most of the town’s citizens believed it was totally justified. They also believed it served as a strong warning and deterrent to criminals in general.

Don’t mess with Red Cliff !