Castle: A Little Town with Big Ambitions

Richard Perske, December 2021

The town of Eagle has not always been known by that name. The small community went through several name changes in the 1880s and 1890s before being incorporated in 1905 and officially becoming the town of Eagle, Colorado.

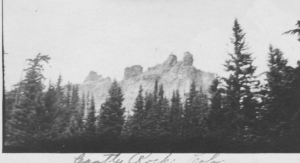

Photo by Alda Borah captures Castle Peak in 1910

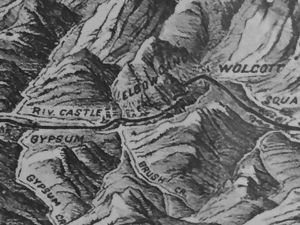

The journey began in 1885 when William Edwards developed a townsite and a U.S. Post Office near the junction of the Eagle River and Brush Creek. Edwards named the settlement “Castle.” The settlement was situated adjacent to Edward’s ranch on a level and nearly treeless rise with a nice view of Castle Peak to the north. Early wagon road access to Castle came from Squaw Creek over Bellyache Ridge and down the fertile Brush Creek Valley.

The arrival of the railroad brought big changes to Castle. Construction of the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad through the lower Eagle River Valley involved thousands of workmen, horses, and mules, creating an economic boom in 1886 and 1887. Edwards envisioned a thriving town serving both the coming railroad, nearby ranches, and the mines of the promising Fulford mining district. Castle eventually passed through a succession of ambitious and wealthy owners whose personal fortunes rose and fell with the value of their silver mines.

A locomotive powers across the railroad bridgeinEagle in the 1930s. The wooden trestle was replaced in 1934.

The 1887 arrival of the railroad connected Castle to the outside world. All railroad facilities were carefully mapped and named to ensure the efficient delivery of passengers, freight, and mail to locations along the tracks. Within four years a series of actions by the D&RG and the U.S. Post Office re-identified the little community of “Castle” as “Eagle” (the more commonly used name). That’s the name that eventually stuck, although there were some in-between names, also.

The D&RG extended tracks 30 miles down valley along the north bank of the Eagle River from the mines at Rock Creek (Gilman) to just above Castle, where a substantial railroad bridge was required to cross the Eagle River. In August 1887, the D&RG established a watering stop and siding near this bridge that it initially named “Eagle River Crossing.” The railroad siding served Castle, the Brush Creek agricultural community, and the new Fulford mining district. All Rio Grande passengers, freight, and mail bound for those destinations were ticketed to “Eagle River Crossing” (not “Castle”). That began the Castle community’s name transitions.

The Colorado Business Directory of 1890 lists Eagle River Crossing with a population of 25.

Clark Wheeler gets involved

In 1891 Aspen millionaire B. Clark Wheeler invested heavily in the Fulford mining district, purchasing Edward’s ranch as well as the original town site of Castle. He believed that centrally-located Castle would soon become the Eagle County seat and planned to build a branch line railroad up Brush Creek to serve his promising mining properties. Wheeler began by enlarging adding and selling additional lots to the Castle community. A.H. (Art) Fulford acted as Wheeler’s “attorney,” on the real estate deals. Fulford was also the construction superintendent for the wagon road from the Brush Creek forks to Fulford. Art and his brother Mont had recently built a modern livery stable in Castle. The Fulford family owned a ranch and stage route “halfway house” located just below the Brush Creek forks (currently the site of the Sylvan Lake Visitor Center).

In 1891 the D&RG upgraded their original siding, adding a station platform with ore bins and renamed it “Eagle Station.” In August 1891 the Post Office name was officially changed from “Castle” to “Eagle.” From this point on the community was universally referred to as Eagle, Colorado.

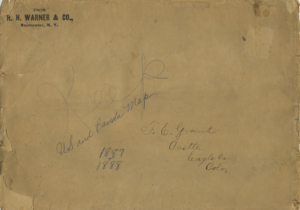

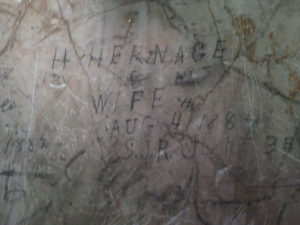

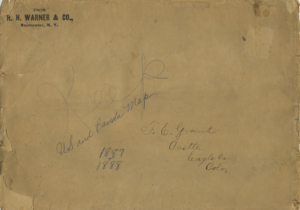

Among the artifacts in the ECHS/EVLD collection is this envelope addressed to F. E. Grant. Note that the writer took care to write the address of both “Castle” and “Eagle” on the envelope, likely ensuring that it would reach its destination during a time of community name transition.

Art Fulford died in a backcountry avalanche on New Year’s Eve Dec. 31, 1891, just as the Fulford mining district and town of Fulford were starting to develop. Many gold mines were dug into the hills around Fulford in 1892 and 1893 but no bonanza ore bodies had been located.

By August of 1893, the Silver Panic and steeply declining silver prices idled many Colorado silver mines and smelters. Lower grades of silver ore could not be mined, transported, and smelted at a profit. Wheeler, facing mounting losses from his Aspen silver mines, sold his Eagle County holdings. Fortunately, he found a newly-made Eagle County millionaire, Alexander Angus McDonald, willing to invest in the still-thriving gold mines. In December 1893 A. A. McDonald bought Wheeler’s enlarged townsite of Castle and took leases and bonds on Wheeler’s Nolan Creek (Fulford area) mines. McDonald also embraced Wheeler’s vision that Castle should become the Eagle County seat. He announced plans to improve his little town by building a “brick block” business section and planting thousands of shade trees.

The McDonald era

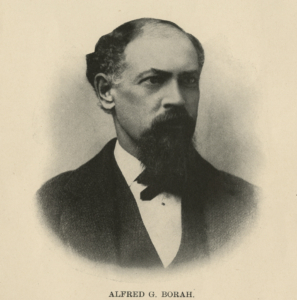

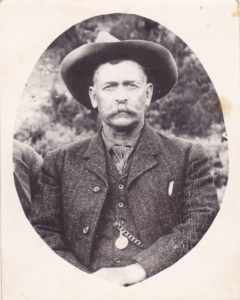

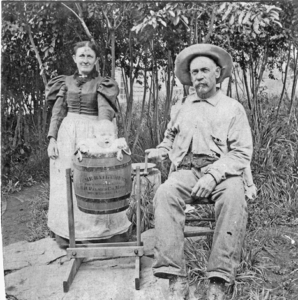

The man on the far right, top row in this late 1890s photo is believed to be Alexander Angus McDonald, who once owned whatis now the town of Eagle.

Born in Canada of Scottish ancestry, McDonald’s path to a miner’s riches had been rocky. In May 1884 his home and boarding house (Glengarry House) in Leadville burned to the ground in a major fire. In June, his wife took their two young daughters back to Silver Cliff and filed for divorce. McDonald was fond of drink and enjoyed a party when he could afford it. He relocated to Battle Mountain and Gilman, taking up small stakes and leases in existing mines. In early 1891 he secured an exclusive lease and bond on the Belden mine, one of the original Battle Mountain mines. The locals considered it to be “a worked-out proposition”. McDonald re-timbered the old workings, re-started production, and explored deeper for new ore bodies. Belden soon began paying off. He also discovered an extremely rich ore body that he blocked out and kept in reserve for future development. The terms of his lease required that a 25% royalty from the Belden’s ore smelter income be paid to the mine owners in Boston. McDonald shrewdly limited his ore production to the tonnage necessary to pay off the bond and acquire full ownership of the Belden. By March 1893 he was the sole owner of the Belden. He then increased ore production and began shipping his richest ores without the need to make royalty payments.

In April 1893 the Leadville newspapers reported that several single carloads of the rich Belden ore set smelter records with returns of over $2,100 each. The money started rolling in. Belden’s amazing success was reported statewide. By June 1893 McDonald’s monthly income was reportedly $75,000 and Belden’s ore reserves were estimated at $1.5 million. During the worst of the 1893 panic the very rich Belden ore could still be produced at a profit. That summer, McDonald kept all the Battle Mountain miners working and on his payroll by getting creative with work shifts. The miners were very grateful for steady work despite smaller paychecks. McDonald became a very popular Gilman millionaire.

BULLY FOR THE BELDEN

It is Keeping all of the Battle Mountain Miners at Work.

The report of the closing down of the Belden mine at Red cliff was an unfortunate error into which our reporters were led. It is not only not closed, but is in full operation and the mainstay of the Battle mountain district, not only giving employment, by rotation, to nearly every miner in camp, but contributing largely toward keeping the American Smelter, in this city, in blast. The owner of the Belden , Mr. A.A. McDonald, has a contract with this concern for sixty tons a day, and is working three eight-hour shifts, employing 120 men, but dividing the work among all of the industrious miners of the district, to the end that none may suffer for the necessaries or be compelled to move out, pending the settlement of the silver question.

Leadville Herald Democrat

August 25, 1893

Now a state senator, B. Clark Wheeler owned the Aspen Times newspaper, the Aspen Mining Stock Exchange, and several silver mines in Aspen. Wheeler had also invested heavily in the Town of Castle and the Nolan Creek Mining Company properties in partnership with A.H. Fulford.

Wheeler was well connected politically and keenly aware of the economic impact of the silver crash and coming recession. He was financially over-extended in mining and land speculation and was absolutely delighted to sell some of his holdings to McDonald.

NEWS OF THE MINES

A.A. McDonald the bonanza owner of the Belden mine at Gilman has proposed to the Aspen Belt Mining and Milling company to sink a big deep shaft on five claims of the company located at Fulford for a $50,000 bond and a three years’ lease. The directors will meet in Aspen today to authorize and execute the papers. J.H. Good, J.A. Campbell, Captain W.F. Kavanagh, and B. Clark Wheeler are the heavy stockholders of the company. Mr. Wheeler has sold the townsite of Eagle and the adjoining ranch to Mr. McDonald, who will soon inaugurate a campaign of improvement at Eagle in the way of a brick block and several thousand shade trees. Next fall the county seat of Eagle county will probably be changed to Eagle.

Aspen Weekly Times

December 2, 1893

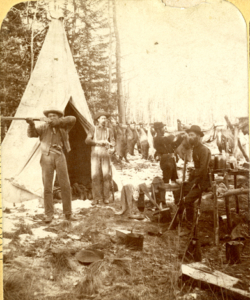

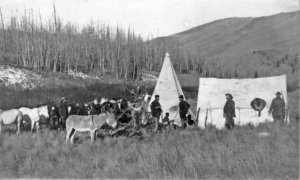

There were just a few buildings in Eagle in the mid-1890s. The tent structure on the left may have been McDonald’s July 4th dance pavilion. The original railroad bridge is on the right, adjacent to the two-story building.

Contrary to popular legend, McDonald did not “buy the town site for back taxes”. He bought the undeveloped town lots from B. Clark Wheeler and paid the back taxes Wheeler owed. Initially Mr. McDonald had very ambitious plans to improve the little community that included his idea for a new name: “McDonald.” In 1894 he had a revised town site land survey prepared, platted, and filed with the Eagle County recorder as the town site of McDonald. However, the post office, D&RG Railroad, and everyone else continued to call the community “Eagle”.

McDonald promotes Eagle

Now connected by the railroad to the world beyond, the community of Eagle would soon be impacted by economic and political events far beyond Colorado. The population of Eagle was still less than 100 with a school enrollment of about 30 students. McDonald devised a grand plan to put Eagle on the map. In 1894 he spared no expense to host a gigantic 4th of July celebration featuring $1,000 in cash prizes for drilling contests, horse races, bicycle races, and even some traditional Scottish athletic contests. McDonald lavishly advertised the event in newspapers statewide and negotiated with the D&RG railroad to provide special half- priced passenger fares. He also constructed a racetrack and erected a large canvas dancing pavilion. It was Flight Days on steroids and a huge crowd was anticipated.

The Eagle Will Scream

Mr. Frank Farnum, general road overseer of Eagle county and an old-time resident of Red Cliff is in the city. “Business has been very quiet with us, but we have tried to forget our troubles and are arranging a gala Fourth of July celebration at Eagle, about thirty-five miles below Red cliff.” said Mr. Farnum. “There is a large force of men at work building a race track, dancing pavilion, etc.”

“Crops in the valley are looking fine and the farmers look for a big season.”

Leadville Herald Democrat

June 28, 1894

In June 1894 Mr. McDonald placed advertisements in almost every newspaper in western Colorado, inviting everyone to Eagle.

Although sizeable crowds were anticipated, the gala event experienced a major last minute problem when railroad labor disputes and riots in Chicago resulted in a rail strike. All rail traffic in western Colorado stopped on July 2, 1894. McDonald’s special trains were not available. The people who did manage to attend reportedly had a very good time.

McDonald the politician

In 1895 McDonald entered the political arena. He vigorously campaigned for the office of State Representative and initiated a special election to move the Eagle County seat.

A petition is being circulated in Eagle county asking for the calling of a special election to change the county seat from Red Cliff to the town of Eagle. A.A. McDonald, the owner of the Belden mine, is the principal mover in the enterprise, having bought the town site from B. Clark Wheeler.

Aspen Weekly Times

June 8, 1895

The county seat question was placed on the November 1895 ballot. At this time Eagle’s population was slightly less than 100. Considering populations of nearly 400 in Red Cliff, 450 in Gilman, and 200 in Minturn, it would seem that little Eagle would not have a chance at winning. However rural voters from Basalt, Gypsum and Brush Creek supported the move to Eagle and there was a rivalry between Red Cliff and more the populous Gilman on Battle Mountain (Mr. McDonald’s home base). Eagle did receive the most votes for the county seat, but lawsuits, injunctions, and court appeals by Red Cliff prevented the move. In 1899, the Colorado Supreme Court ruled that the 1895 county seat special election was unconstitutional because voting had been limited to “taxpayers,” preventing many from voting. That decision ended the first legal battle in what became a 25 year long Eagle County seat war between Red Cliff and Eagle.

McDonald also ran for office as State Representative on the Republican ticket in 1895 but was narrowly defeated.

In December 1895 Mr. McDonald sold one-half interest in the Belden mine for $600,000 and turned the mine’s daily management over to the buyers. He then began investing in mining property and real estate, but lady luck had deserted him. Within a few years his lavish spending, generous loans, and speculative mining investments exhausted his fortune. He advertised his remaining lots in Eagle for sale and listed Frank Doll (another prominent Eagle County pioneer) as his real estate agent.

McDonald had remarried in 1895 and was the father of two small children when he suddenly died of pneumonia at Gilman on April 3, 1899, at the age of 43. His death was reported statewide and his large funeral service in Red Cliff was well attended. McDonald had recently taken another mining lease on Battle Mountain and was anticipating a big strike and a financial comeback. His obituary noted that McDonald’s unbounded generosity and his boastful “gasconading” style had contributed to his downfall. He had always been a gambler and risk taker. He began as a miner working for wages. The Belden bonanza, his ultimate success, made him a millionaire for a few short years before he gambled it all away.

Eagle finally became the county seat in 1921, ending the bitter 26-year war that A. A. McDonald had so eagerly started. The bonanza owner of the Belden did win in the end and a much larger town of Eagle, once a pioneer community named “Castle,” marked its 100th year as the Eagle County seat in 2021, thanks to efforts and ambitions of Alexander Angus McDonald.