Holy Cross City: The gold camp built on hope, by Kathy Heicher

(Note: This story first appeared in the Winter 2023 edition of Vail Valley Magazine.)

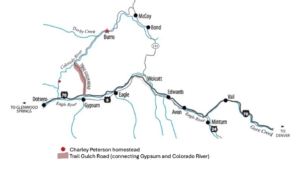

The first hint that there was gold embedded in the geology of the Eagle River Valley appeared in 1874 via scribbled notes in explorer Ferdinand Hayden’s famed survey. In that document, geologists noted that men fishing the tributaries coming into the Eagle River from the south (Homestake Creek, Cross Creek, Beaver Creek, and Lake Creek) were finding placer gold in the gravel. That news prompted the quiet filing of a few mining claims.

However, on July 8, 1880, the Leadville Herald-Democrat newspaper reported that an experienced prospector, J.W. Lynch, had arrived in town with a 60 pound lump of ore to be processed. Lynch revealed his discovery of a gold-bearing quartz vein above timberline in the wild country southeast of the famous Mount of the Holy Cross.

The newspaper called for development of a new camp and mining district. Prospectors heeded that advice. Five weeks later, scores of miners had flocked to the area, filing enough claims to warrant the formation of the Holy Cross Mining District. The district (a governing entity) encompassed the headwaters of Cross Creek and Homestake Creek and about 100 square miles of the wild country in between.

Located at an elevation of 11,335 feet, Holy Cross City was a gold mining camp that was expected to boom when it first developed in 1880. However, low quality ore, expensive processing, and brutal winters turned the camp into a ghost town by 1884.

Mining camps populated by adventurous miners sprang up throughout the mountainous district. Among the most prominent of those camps was Holy Cross City. Located at an elevation of 11,335 foot in a meadow on the east slope of French Mountain, this headline-generating yet short-lived mining camp was the product of unfettered human optimism and the harsh reality of a shallow ore vein.

Creating the camp

Holy Cross City’s first year, 1881, was a time of development and splashy headlines. Newspapers described country “seamed with inexhaustible fissure veins of gold ore.” Even the names of the mining claims were infused with optimism: Grand Trunk, Solid Muldoon, Shamrock, Treasure Vault, Hunky Dory, and the Eureka.

Miners stayed in a boarding house or in private cabins. Most of the mining took place in the summer, although a small crew of 24 men stayed for the winter.

In a relatively short amount of time, newspapers reported there were 25 buildings in the camp including a boarding house, post office, two general stores, assay office, blacksmith shop, a drug store, and several saloons. Two rows of residential cabins faced each other on either side of a short “street.” By 1882, the Colorado Business Directory reported a population of 200 people in Holy Cross City. There was talk of forming a school district. A sister mining camp, Gold Park, located four miles down the road claimed 400 residents. A flume with a cast-iron bottom connected the two camps. In theory, water in the flume would carry smashed ore from Holy Cross City to Gold Park for processing. However, there were issues with the grade of the flume, and the ore chunks tended to pile up unless a team of miners kept things moving.

Initially the ores extracted from the district were promising, with assay results convincing speculators that the “Mother Lode” could be located by just digging a little deeper. The Gold Park Mining and Milling Company was formed in 1881 and was incorporated with $500,000 in capital stock. Professional engineers and mine managers were recruited. The company gained control of 23 of the mining claims on French Mountain and put a large crew of miners to work.

“There are a great number of good properties in all parts of the district that would pay well if properly worked … we expect to see lively times among the gold mines of the Holy Cross District.”

Rocky Mountain News

June 9, 1882

During the initial mining boom, 400 men were employed in the mines at Holy Cross City.Gold was the ore that prompted the development of the mining camp in 1880, however, a “rich silver vein” was reported at Holy Cross in 1882.

But mine speculators often tend to be captured by the promise of riches, while ignoring reality. The unfortunate truth about most of the Holy Cross Mining District was that while the upper few feet of the ore veins were promising, the quality of the gold deteriorated quickly at deeper levels. Ore in the upper two feet of the vein assayed out at $100 per ton. But at the next lower level, the gold was mixed with pyrite, requiring more complex processing. The value dropped to $40 feet per ton. Two feet lower, the ore’s value was a mere $9 per ton. This scenario proved typical of the veins throughout the district.

One miner, apparently well aware of the peculiar nature of the Holy Cross district ore veins, dug several shallow holes along his claim. Of course, the upper level ore yielded assay results attractive enough to prompt a purchase offer of $50,000 from an Eastern capitalist. The investor paid half of the money up front, intending to pay the rest upon development. The seller took the initial $25,000 and disappeared … and is credited with being the only man to make a clear profit from the mines of the Holy Cross District.

Rough and rowdy

Visitors could find a room and meals at the Timberline Hotel. The camp also boasted a post office, general merchandise store, assay office, and a justice of the peace. The trip from Red Cliff to Holy Cross City involved traveling over 12 miles of rough road and could involve several days during the winter.

Mining camps, dominated by men with plentiful saloons tended to be rowdy and sometimes violent. A double murder at Holy Cross City made headlines in the Leadville papers on Dec. 10, 1881.

Economic issues were likely the start of tensions between the working miners and the Gold Park mines superintendent, Mr. Turney, and mine foreman Harry Weston. Disgruntled miners made threats against the two men, prompting Turney to abruptly discharge 150 men. Many men left the camp immediately, but several heavily armed and angry ex-employees remained in the camp and threatened vengeance. In response, the mine operators organized a “vigilance committee” of 40 armed men to protect the mines.

One angry miner identified only as “Bagley,” shot and killed Weston, fired another shot at Turney, then fled to his cabin, pursued by the vigilantes who fired shots into the building. Bagley was fatally wounded. The coroner ruled his death a suicide.

That same day, somebody sent one of the laid-off miners, Jack White, a notice to leave the camp immediately. The angry White procured three revolvers, then proceeded to walk down Holy Cross City’s only street with a cocked gun in each hand and the third revolver in his belt, cursing and demanding to know exactly who had sent the notice.

The armed members of the vigilance committee lined either side of the street, prepared to shoot White down. Undeterred, White remained in the town two or three hours, then departed for Leadville.

The camp was in an uproar. The frightened night foreman of the mine, Bill Bates, locked himself in his cabin and refused to come out. Turney continued to order the laid-off miners to leave town. The newspaper rather gleefully predicted that “the prospect is excellent that one or two more killings will crimson the annals of that camp within the next week.”

Apparently, by 1883, things had settled down notably in the Holy Cross Camp. On April 18, 1883, the Rocky Mountain News reported, “The morals of the place are above the average of mining camps since the output of the mines has never been enough to attract the vicious elements which usually invade thrifty camps.”

The lady miner

Perhaps the most unusual miner to work the Holy Cross District was Mrs. Julia Edith Dunn, the daughter of an old and distinguished family from the East. Well educated and reared in luxury, Dunn excelled in music and painting. Newspaper reports suggest that a combination of health issues and a failed marriage prompted her to head west with her children. Deeply religious, she chose Holy Cross City as her destination. There she found a cabin and made enough money teaching music and painting lessons to file several mining claims. She hired a couple of miners and worked alongside them to develop the claims.

Two of the claims yielded gold and silver. When Dunn overheard her hired hands plotting to steal the nuggets, she procured a pistol, guarded the ore throughout the night, and sent the men packing to Red Cliff. Dunn sold her claims for a tidy profit, then invested that money in lodes closer to Red Cliff and Leadville. One of her mines was predicted to yield a minimum profit of $500,000. In a camp dominated by rough men, she was notable.

“Any mining man in the west might well be proud of what this woman has accomplished and considering he almost insurmountable difficulties she has had to overcome , the years of toil and struggle in the mountains, her achievements deserve to rank among the greatest in the state.”

Herald Democrat

Jan. 1, 1904.

From boom camp to ghost town

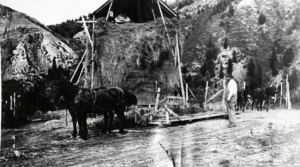

A freight wagon driver steers a wagon full of ore to the crusher at Holy City. The wagon and horses are traveling on a wooden driveway. The processing mills at Holy Cross City and Gold Park serviced many mining claims in the Holy Cross District. The Treasure Vault, Little Mollie, and Pelican mines were among the most productive mines.

Although a few of the Holy Cross mines were briefly profitable, the area was never destined for great mining success. Mine profit depended upon the ability to process the mines at the site (rather than hauling wagonloads of heavy ore great distances). Unfortunately, most of the ore in the district was laced with pyrite, which could not be separated from the gold by any simple process.

The remoteness of Holy Cross City made accessibility difficult. A 12-mile road connected the camp to Red Cliff. However, in winter the snow depths were daunting. An attempt to move a woman and her two children from Red Cliff to Holy Cross City in February involved three days of precarious travel, eight horses, two sleds, and 10 men to help break a trail through the snow.

Although the mines bustled in the summer, in the winter only small crews attempted to stay in the camp. The cold weather and isolation took a toll.

“Fred went down to Gold Park today after our washing [laundry]. He sent it to Red Cliff in about the middle of January. The weather has been so rough that we could not get it before. I wish I was through with this blasted country.”

Letter from an unnamed miner

March 7, 1885

Holy Cross City

By 1883, the Gold Park Mining Company acknowledged that the quality of ore was not sufficient to justify further investment in the area. The company pulled out, as did most of the miners. In 1884, the director of the Denver Mint reported that only $6,400 of ore had been produced by the entire district. By the end of that year, Holy Cross City was a ghost town.

The mining company made a couple of attempts to revive the mines, and the local newspapers optimistically predicted that the area would boom again. However, the issues of ore quality, impassible roads, and high elevation living prevailed.

The Leadville Daily Chronicle reported on Aug. 5, 1890, that the camps of old Park and Holy Cross City were practically deserted.

“… were it not for a few hearty prospectors and miners who are now working among the mountains, the wolves and mountain lions would stalk the silent streets, monarchs of all they survey. “

Leadville Daily Chronicle

Aug. 5, 1890

Yet, that same newspaper, noting that the mining company had abandoned over $200,000 in machinery at the site, predicted that men would soon figure out how to effectively process the ore, and that the Holy Cross District would once again boom. Although a few optimistic miners continued to explore the country, there was no second boom.

These days, Holy Cross City is accessible by hiking or very skilled four-wheel vehicle driving. The remains of several buildings are scattered through the high country meadow. It remains a wild and beautiful country, with a history that captures the imagination.

Perhaps the true story of the Holy Cross District was best captured by a man with the initials “J.M.K.” who wrote a letter to the Herald Democrat newspaper on June 22, 1902, following a fishing trip in the Holy Cross District:

The whole of the ground on each side of the creek will pan gold, from Red Cliff to Gold Park … several claims were worked, but none were ever found from which even wages were taken out. The fishing, however, on the creek was far better than the placer mining.”

END

(Editor’s note: Kathy Heicher is the president of the Eagle County Historical Society and the award-winning author of four local history books. She “mined” the archives of the ECHS, Eagle Valley Library District, History Colorado, and Denver Public Library in researching this story.)